|

|

History of AstronomyChinaAstronomy in ancient China |

|

Chinese myths and legends around stars, planets and constellations are as old as

Chinese astronomy, which dates back to the second millennium BC, the Chinese Bronze Age

and the Shang dynasty.

|

The primary focus of this site is not astronomy, but Star Lore, which is folklore based upon the stars and star patterns. We try

to create a collection of mythical stories about stars and constellations from all over the world. However, to better understand and interpret the stories,

a brief history of the astronomy of different cultures might be helpful.

This is by no means a scientific paper on the history of Chinese astronomy, but merely a collection of illustrated highlights of that history, along with some links to what we think are reliable sources on the subject.  Ian Ridpath and Wikipedia both provide excellent summaries of ancient Chinese astronomy. |

Four Quadrants of Chinese astronomy Source: NIx's Mixed Bag |

|

|

This portion of our site is about the history of ancient Chinese astronomy.

Click here to discover the world of Chinese Star Lore. |

Bits of History of Chinese Astronomy |

|

|

Xishuipo Tomb (ca 4000 BC)

A tomb associated with the Yangshao culture was excavated in 1987 in

Puyang.

|

Xishuipo M45 Tomb Source: The Apricity |

|

|

Taosi Observatory (ca 2100 BC)

An archaelogical site in North China, associated with the neolithic Longshan culture

contains one of the oldest astronomical observatories,

used to observe the sunrise at the summer and winter solstices.

|

Taosi Observatory Source: China Daily |

|

|

First observed Solar Eclipse (2165 - 2128 BC)

Shūjīng, the ancient Chinese Book of Documents records that "... in the first day of the

last month of Autum, the Sun and the Moon did not meet harmoniously in Fang. The blind beat their drums, the inferiour officers galloped and the

common people ran about."

|

Tiangou, the Heavenly Dog; Source: Pearl River |

Most Sources go for October 22, 2137 and link the event to the legend of astronomers Ho and Hi (see below).

Source: W. S. Tsu: A statistical survey of solar eclipses in Chinese history |

|

|

Astronomers Ho and Hi (2137 BC) A Chinese legend dates the observation of solar eclipses in China back to the 3rd millennium BC. According to the legend, royal astronomers Ho and Hi dedicated too much of their time to consuming alcohol and failed to predict a forthcoming eclipse that occurred on the first day of the month, in the last month of autumn in 2137 BC. |

Ho and Hi; Source: Hong Kong Space Museum |

The emperor became very unhappy because, without knowing that there was an eclipse coming, he was unable to organize teams to beat drums and shoot

arrows in the air to frighten away the invisible dragon.

The Sun did survive, but the two astronomers lost their heads for such negligence. Since then, a legend arose that no one has ever seen an astronomer drunk during an eclipse.  Source: astronomytoday.com |

|

|

Shang Oracle Bone (ca. 1300 BC)

Oracle bones were pieces of ox scapula or turtle plastron, which were used for a form of divination

in ancient China, mainly during the late Shang dynasty.

|

|

|

|

The Five Agents of the Sky (ca. 650 BC)

Chinese culture regarded all celestial objects as living beings, most of them more or less look like humans. Five paintings created by an unknown

artist during the first half of the Tang Dynasty (618–690) show the five then known planets, envisioned as human beings.

|

Jupiter as a celestial immortal Source: All Things Chinese |

|

|

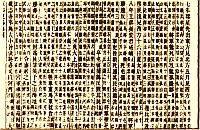

Xing Jing Star manual (ca. 350 BC)

Astronomer Shi Shen is credited with the creation Xing Jing, a star catalogue containing

93 Constellations and the names of 810 stars, 121 of which are catalogued with their location.

|

Copy of Xing Jing Guide to Astronomy; 1790 Source: World Digital Library |

|

|

First sighting of Halley's Comet (240 BC)

The Records of the Grand Historian, a monumental history of ancient China

and the world, finished around 94 BC by the Han dynasty official Sima Qian contains a record

of a comet sighted in 240 BC.

|

Report of the 240 BC apparition of Halley's Comet from the Shiji Source: Wikipedia |

|

|

Mawangdui Tomb (ca 177 BC)

Another early record, containing images and descriptions of 29 different comets was found in a tomb in

Mawangdui. This text can be solidly dated as being prior to 168 BC, the date assigned to the

tomb. It may be associated with a similar astronomical text from the same tomb, which details planetary motions for the seventy years ending 177 BC.

|

|

|

|

Wukaiming Tomb (ca. 25-220 AD)

An engraving dated to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD) shows the complete constellation of the

Big Dipper part of Ursa Major including

Alcor (ζ2 UMa), the fainter double-star companion of

Mizar (ζ1 UMa). The stars form the Emperor's cart in the heavens.

|

The Emperor's cart, 25-220 AD Source: University in Beijing |

|

|

The Supernova of 125 AD

In the year 125 AD, during the Han Dynasty, Chinese astronomers described a "Guest Star" - the

ancient Chinese term for a supernova. It "resembled a bamboo mat" and was visible in the night sky for eight months.

|

Chitasei Go Yō, a fictional astronomer from the Han period Source: Atlas Obscura |

|

|

|

|

Supernovae of 1006 and 1054

Between April 30 and May 1, 1006, in the constellation now known as Lupus, a

supernova appeared. Most likely, it was the brightest supernova in recorded human history.

|

Zhou Keming and the 1006 supernova Source: ancientpages.com |

Another supernova appeared around July 5, 1054. Chines astrologer Yang Weide wrote about the

sighting:

I humbly observe that a guest star has appeared; above the star there is a feeble yellow glimmer. If one examines the divination regarding the Emperor, the interpretation is the following: The fact that the star has not overrun Bi and that its brightness must represent a person of great value.  Sources: Wikipedia |

|

|

Xinyi Xiangfayao (1092)

In 1092, Chinese scientist Su Song published a treatise called Xinyi Xiangfayao. Although the

writings were mostly about clock towers, they contained five star maps, which today are the oldest star charts in printed form.

|

|

|

|

|

Suzhou Planisphere (1193)

The circular chart from Suzhou was first drawn around 1193 and was later in 1247 engraved on a limestone stela.

It laid the foundation to a constellation system that is still used today. The chart divides the sky into

twenty-eight Mansions, reflecting the movement of the Moon around the Earth through a

sidereal month (27.32-days).

|

Reproduction of the Suzhou star chart Source: Wikipedia: Chinese Constellations |

|

|

Xu Guangqi (1562 – 1633)

Astronomer, agronomist, mathematician, and writer was not only a multi-talented scientist but also an important politician during the

Ming Dynasty. As a converted Jesuit, his long-lasting relationship with fellow

Jesuit Matteo Ricci was the first scientific East-West colaboration.

|

|

|

Copernicus and the Forbidden City (1601)

In 1582, Italian Jesuite priest Matteo Ricci arrived in Macau to work at the

Jesuit China mission which was founded in 1552.

|

Matteo Ricci with Xu Guangqi

Matteo Ricci with Xu GuangqiSource: Wikimedia |

|

Eclipse Competition on the Chinese imperial court (1629)

In 1601, Italian Jesuit priest and scientist Matteo Ricci became the advisor in matters of

astronomy and calendrical science to the Chinese Emperor (see here

for details). In 1610, he was succeeded by Nicolò Longobardo.

|

|

|

The Southern Asterisms (1629)

Work on the new calendar, which would later be known as the Chongzhen Calendar was

carried out by German Jesuits Johann Schreck and

Johann Adam Schall von Bell, together with Chinese Jesuite

Xu Guangqi, the one who started the scientific East-West collaboration with

Matteo Ricci almost three decades earlier (see

here for details).

|

|

|

|

Quing Dynasty Globe (1673)

A bronze celestial globe showing the Chinese constellations was manufactured in 1673 for the ancient Beijing Observatory.

|

Quing Dynast Globe University of Maine Farmington |

The Chinese Sky |

In ancient Chinese astronomy, the circumpolar stars (visible throughout the year) were divided into

Three Enclosures, the the northernmost one being the

Purple Forbidden Enclosure, followed by the Supreme Palace Enclosure and the Heavenly Market Enclosure.

The region along the ecliptic was divided into four directions, the Azure Dragon of the East, the Black Tortoise of the North, the White Tiger, of the West and the Vermilion Bird of the South. These constellation were visible only during parts of the year.  The four directions were divided further into 28 Lunar Mansions.  The links below lead to descriptions of each of these sections. |

|